About

Chess is a board game played between two players. It is sometimes called Western chess or international chess to distinguish it from related games such as xiangqi and shogi. The current form of the game emerged in Spain and the rest of Southern Europe during the second half of the 15th century after evolving from chaturanga, a similar but much older game of Indian origin. Today, chess is one of the world’s most popular games, played by millions of people worldwide.

Left to right: white king, black rook, black queen, white pawn, black knight, white bishop

Chess is an abstract strategy game and involves no hidden information. It is played on a square chessboard with 64 squares arranged in an eight-by-eight grid. At the start, each player (one controlling the white pieces, the other controlling the black pieces) controls sixteen pieces: one king, one queen, two rooks, two bishops, two knights, and eight pawns. The object of the game is to checkmate the opponent’s king, whereby the king is under immediate attack (in “check”) and there is no way for it to escape. There are also several ways a game can end in a draw.

Organized chess arose in the 19th century. Chess competition today is governed internationally by FIDE (International Chess Federation). The first universally recognized World Chess Champion, Wilhelm Steinitz, claimed his title in 1886; Magnus Carlsen is the current World Champion. A huge body of chess theory has developed since the game’s inception. Aspects of art are found in chess composition, and chess in its turn influenced Western culture and art and has connections with other fields such as mathematics, computer science, and psychology.

One of the goals of early computer scientists was to create a chess-playing machine. In 1997, Deep Blue became the first computer to beat the reigning World Champion in a match when it defeated Garry Kasparov. Today’s chess engines are significantly stronger than the best human players, and have deeply influenced the development of chess theory.

This article uses algebraic notation to describe chess moves.

Rules

Main article: Rules of chess

The rules of chess are published by FIDE (Fédération Internationale des Échecs), chess’s international governing body, in its Handbook.[1] Rules published by national governing bodies, or by unaffiliated chess organizations, commercial publishers, etc., may differ in some details. FIDE’s rules were most recently revised in 2018.

Chess pieces are divided into two different colored sets. While the sets may not be literally white and black (e.g. the light set may be a yellowish or off-white color, the dark set may be brown or red), they are always referred to as “white” and “black”. The players of the sets are referred to as White and Black, respectively. Each set consists of 16 pieces: one king, one queen, two rooks, two bishops, two knights, and eight pawns. Chess sets come in a wide variety of styles; for competition, the Staunton pattern is preferred

The game is played on a square board of eight rows (called ranks) and eight columns (called files). By convention, the 64 squares alternate in color and are referred to as light and dark squares; common colors for chessboards are white and brown, or white and dark green.

The pieces are set out as shown in the diagram and photo. Thus, on White’s first rank, from left to right, the pieces are placed in the following order: rook, knight, bishop, queen, king, bishop, knight, rook. On the second rank is placed a row of eight pawns. Black’s position mirrors White’s, with an equivalent piece on the same file. The board is placed with a light square at the right-hand corner nearest to each player. The correct positions of the king and queen may be remembered by the phrase “queen on her own color” ─ i.e. the white queen begins on a light square and the black queen on a dark square.

In competitive games, the piece colors are allocated to players by the organizers; in informal games, the colors are usually decided randomly, for example by a coin toss, or by one player concealing a white pawn in one hand and a black pawn in the other, and having the opponent choose.

Movement

White moves first, after which players alternate turns, moving one piece per turn, except for castling, when two pieces are moved. A piece is moved to either an unoccupied square or one occupied by an opponent’s piece, which is captured and removed from play. With the sole exception of en passant, all pieces capture by moving to the square that the opponent’s piece occupies. Moving is compulsory; a player may not skip a turn, even when having to move is detrimental.

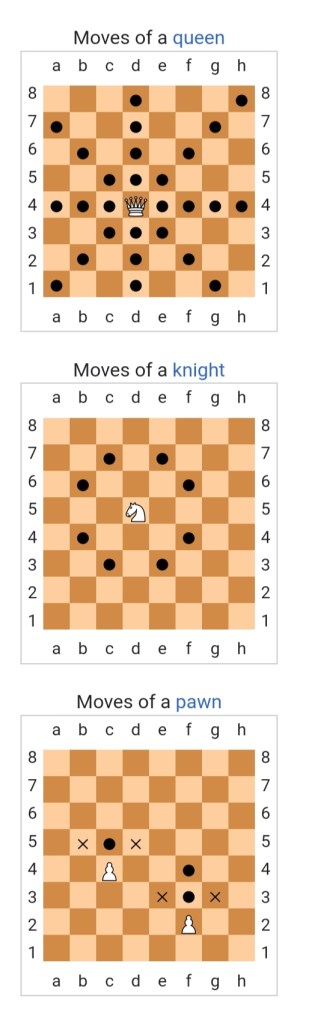

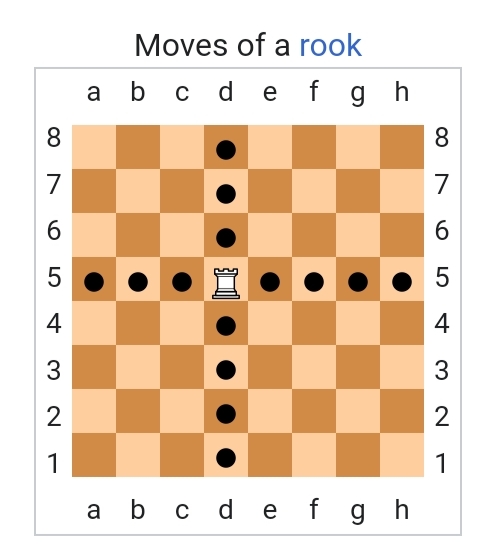

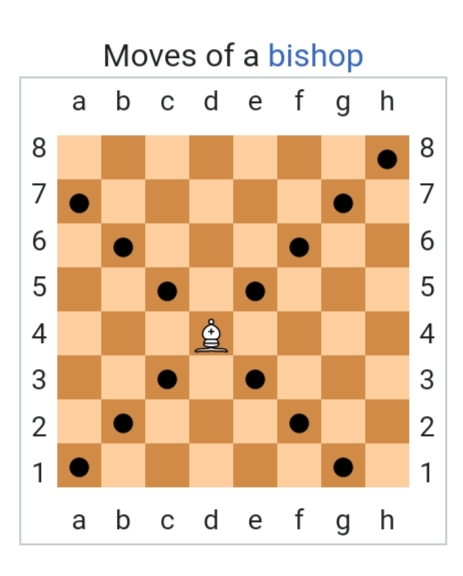

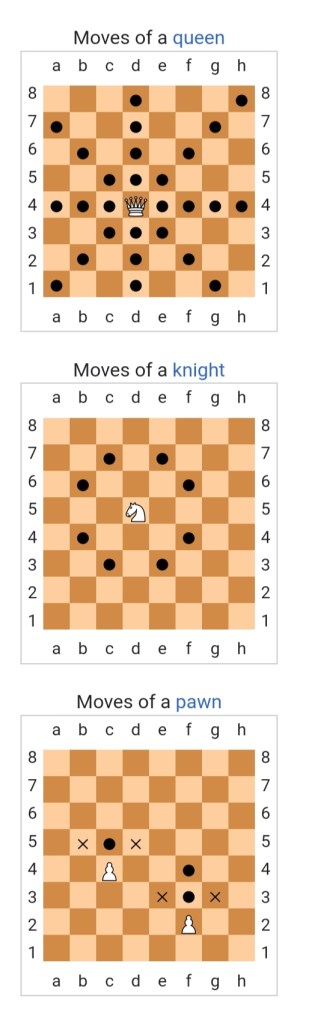

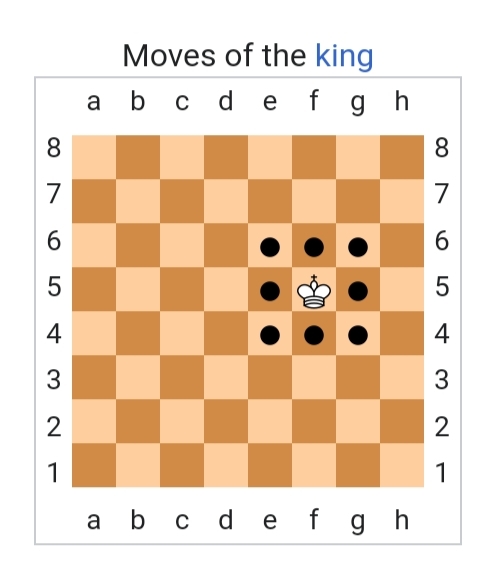

Each piece has its own way of moving. In the diagrams, the dots mark the squares to which the piece can move if there are no intervening piece(s) of either color (except the knight, which leaps over any intervening pieces). All pieces except the pawn can capture an enemy piece if it is located on a square to which they would be able to move if the square was unoccupied. The squares on which pawns can capture enemy pieces are marked in the diagram with black crosses.

The king moves one square in any direction. There is also a special move called castling that involves moving the king and a rook. The king is the most valuable piece — attacks on the king must be immediately countered, and if this is impossible, immediate loss of the game ensues (see Check and checkmate below).

A rook can move any number of squares along a rank or file, but cannot leap over other pieces. Along with the king, a rook is involved during the king’s castling move.

A bishop can move any number of squares diagonally, but cannot leap over other pieces.

A queen combines the power of a rook and bishop and can move any number of squares along a rank, file, or diagonal, but cannot leap over other pieces.

A knight moves to any of the closest squares that are not on the same rank, file, or diagonal. (Thus the move forms an “L”-shape: two squares vertically and one square horizontally, or two squares horizontally and one square vertically.) The knight is the only piece that can leap over other pieces.

A pawn can move forward to the unoccupied square immediately in front of it on the same file, or on its first move it can advance two squares along the same file, provided both squares are unoccupied (black dots in the diagram). A pawn can capture an opponent’s piece on a square diagonally in front of it by moving to that square (black crosses). It cannot capture a piece while advancing along the same file. A pawn has two special moves: the en passant capture and promotion.

Check and checkmate

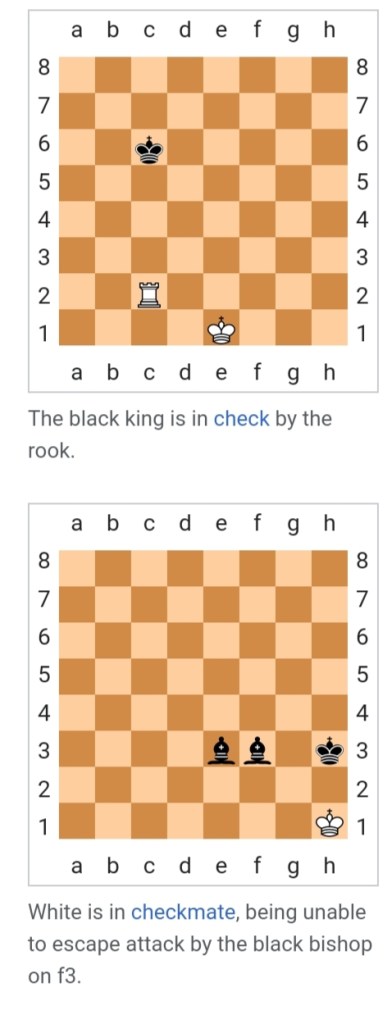

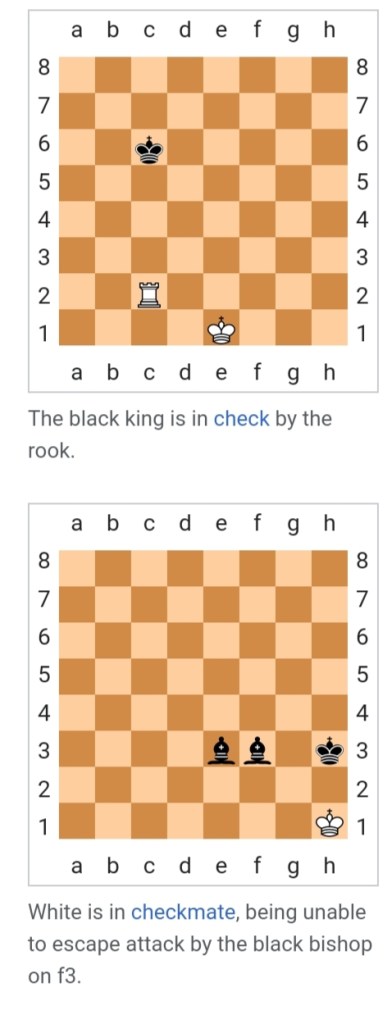

When a king is under immediate attack, it is said to be in check. A move in response to a check is legal only if it results in a position where the king is no longer in check. This can involve capturing the checking piece; interposing a piece between the checking piece and the king (which is possible only if the attacking piece is a queen, rook, or bishop and there is a square between it and the king); or moving the king to a square where it is not under attack. Castling is not a permissible response to a check.

The object of the game is to checkmate the opponent; this occurs when the opponent’s king is in check, and there is no legal way to get it out of check. It is never legal for a player to make a move that puts or leaves the player’s own king in check. In casual games, it is common to announce “check” when putting the opponent’s king in check, but this is not required by the rules of chess and is not usually done in tournaments.

Castling

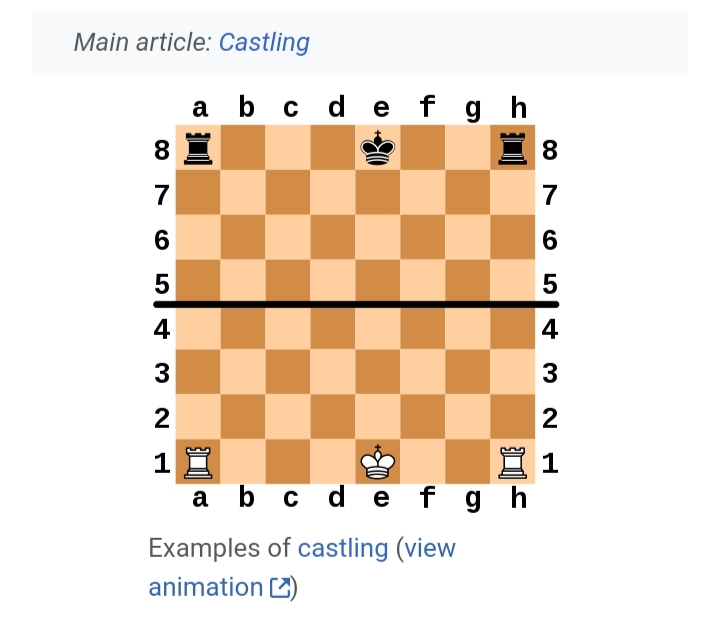

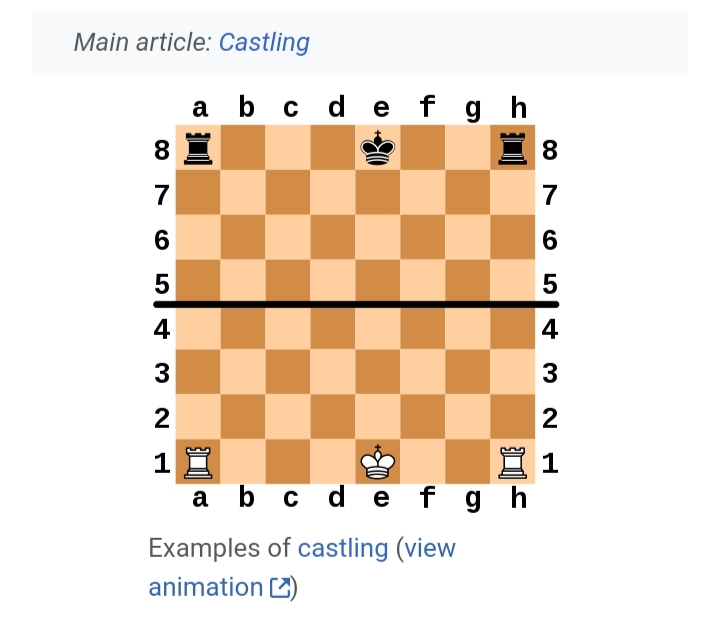

Once per game, each king can make a move known as castling. Castling consists of moving the king two squares toward a rook of the same color on the same rank, and then placing the rook on the square that the king crossed.

Castling is permissible if the following conditions are met:

1)Neither the king nor the rook has previously moved during the game.

2)There are no pieces between the king and the rook.

3)The king is not in check and does not pass through or land on any square attacked by an enemy piece.

Castling is still permitted if the rook is under attack, or if the rook crosses an attacked square.

En passant

Main article: En passant

(left) promotion; (right) en passant

When a pawn makes a two-step advance from its starting position and there is an opponent’s pawn on a square next to the destination square on an adjacent file, then the opponent’s pawn can capture it en passant (“in passing”), moving to the square the pawn passed over. This can be done only on the turn immediately following the enemy pawn’s two-square advance; otherwise, the right to do so is forfeited. For example, in the animated diagram, the black pawn advances two squares from g7 to g5, and the white pawn on f5 can take it en passant on g6 (but only immediately after the black pawn’s advance).

Promotion

Main article: Promotion (chess)

When a pawn advances to its eighth rank, as part of the move, it is promoted and must be exchanged for the player’s choice of queen, rook, bishop, or knight of the same color. Usually, the pawn is chosen to be promoted to a queen, but in some cases, another piece is chosen; this is called underpromotion. In the animated diagram, the pawn on c7 can be advanced to the eighth rank and be promoted. There is no restriction on the piece promoted to, so it is possible to have more pieces of the same type than at the start of the game (e.g., two or more queens). If the required piece is not available (e.g. a second queen) an inverted rook is sometimes used as a substitute, but this is not recognized in FIDE sanctioned games.

End of the game

Win

A game can be won in the following ways:

Checkmate: The king is in check and the player has no legal move. (See check and checkmate above)

Resignation: A player may resign, conceding the game to the opponent. Most tournament players consider it good etiquette to resign in a hopeless position.

Win on time: In games with a time control, a player wins if the opponent runs out of time, even if the opponent has a superior position, as long as the player has a theoretical possibility to checkmate the opponent were the game to continue.

Forfeit: A player who cheats, violates the rules, or violates the rules of conduct specified for the particular tournament can be forfeited. Occasionally, both players are forfeited.

Draw

There are several ways a game can end in a draw:

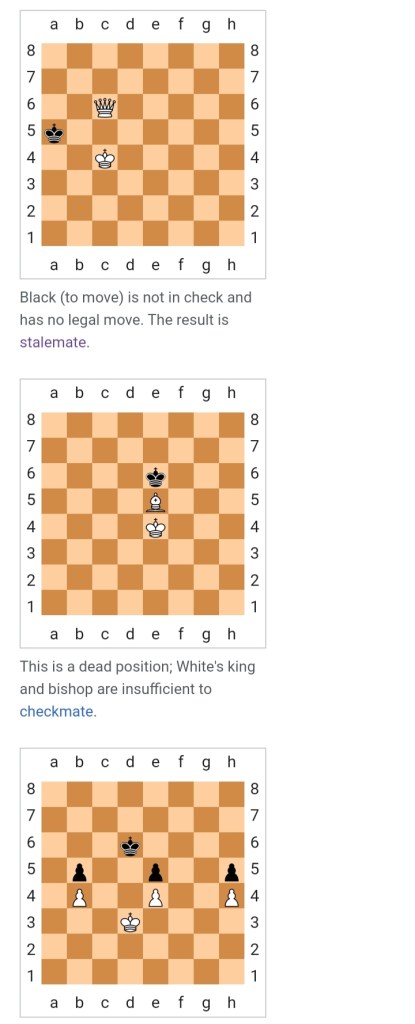

Stalemate: If the player to move has no legal move, but is not in check, the position is a stalemate, and the game is drawn.

Dead position: If neither player is able to checkmate the other by any legal sequence of moves, the game is drawn. For example, if only the kings are on the board, all other pieces having been captured, checkmate is impossible, and the game is drawn by this rule. On the other hand, if both players still have a knight, there is a highly unlikely yet theoretical possibility of checkmate, so this rule does not apply. The dead position rule supersedes the previous rule which referred to “insufficient material”, extending it to include other positions where checkmate is impossible, such as blocked pawn endings where the pawns cannot be attacked.

Draw by agreement: In tournament chess, draws are most commonly reached by mutual agreement between the players. The correct procedure is to verbally offer the draw, make a move, then start the opponent’s clock. Traditionally, players have been allowed to agree to a draw at any point in the game, occasionally even without playing a move; in recent years efforts have been made to discourage short draws, for example by forbidding draw offers before move thirty.

Threefold repetition: This most commonly occurs when neither side is able to avoid repeating moves without incurring a disadvantage. In this situation, either player can claim a draw; this requires the players to keep a valid written record of the game so that the claim can be verified by the arbiter if challenged. The three occurrences of the position need not occur on consecutive moves for a claim to be valid. The addition of the fivefold repetition rule in 2014 requires the arbiter to intervene immediately and declare the game a draw after five occurrences of the same position, consecutive or otherwise, without requiring a claim by either player. FIDE rules make no mention of perpetual check; this is merely a specific type of draw by threefold repetition.

Fifty-move rule: If during the previous 50 moves no pawn has been moved and no capture has been made, either player can claim a draw. The addition of the seventy-five-move rule in 2014 requires the arbiter to intervene and immediately declare the game drawn after 75 moves without a pawn move or capture, without requiring a claim by either player. There are several known endgames where it is possible to force a mate but it requires more than 50 moves before a pawn move or capture is made; examples include some endgames with two knights against a pawn and some pawnless endgames such as queen against two bishops. Historically, FIDE has sometimes revised the fifty-move rule to make exceptions for these endgames, but these have since been repealed. Some correspondence chess organizations do not enforce the fifty-move rule.

Draw on time: In games with a time control, the game is drawn if a player is out of time and no sequence of legal moves would allow the opponent to checkmate the player.